Stage, Theatre & TV9th September 2015

Bravo RSC in Setting New Standards of BSL Integration into Stage Plays!

For the first time ever, the Royal Shakespeare Company offer fully inclusive play to Deaf BSL audience in Stratford

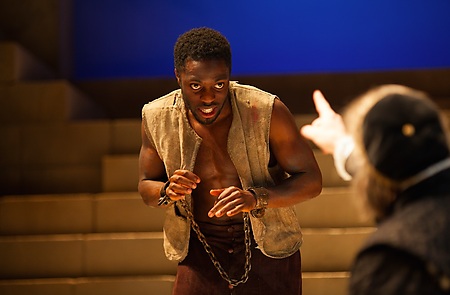

Visual, vivacious and vexing, the Royal Shakespeare Company’s BSL interpreted performance of Christopher Marlowe’s, The Jew of Malta, left me with goose bumps it was so good. Expectations I had from seeing a fully integrated BSL version of a Winter’s Tale recently, were far exceeded by the brilliance of the acting, the directing of Justin Audibert, not to mention the outstanding and delightful Becky Allen who provided a simply beautiful BSL interpretation for the Deaf people in the audience.

Before the night of the show, I had made arrangements to attend with some of the staff at the RSC. Information provided beforehand, including a BSL flyer for the show and then a BSL video showing me the sign names that would be used for each of the characters, allowed me to familiarise myself with them, and made for far more effective translation during the play. For this first ever BSL integrated show at the home of the RSC in Stratford-upon-Avon, Deaf theatre goers were able to book specially allocated seats on-line that provided ready access to the interpreter, and whilst this will rarely provide perfect line of sight throughout with characters coming and going and moving around on stage, it was good to see proper consideration had been made.

During the day, a BSL interpreted tour of the theatre was held, with some of the Deaf people involved asked to watch a rehearsal of the show to make sure they were happy with the seating arrangements. Chatting to people who had done the tour before the show started, they seemed really happy with the arrangements that had been made for them.

Taking my seat on the ground level, to the centre and slightly below the level of the stage, I was struck by the intimacy of the Swan Theatre, a beautiful wooden framed hexagon style auditorium, with two raised galleries above me, every area providing excellent viewing of the stage. Built on the side of the larger Royal Shakespeare Theatre, the Swan holds about 450 people, and for this, the last night of The Jew of Malta, it was fitting that it was a sell out. Having been refurbished as part a larger £112.8 million project, the Swan is often used for playing the works of William Shakespeare’s contemporaries and other European writers, as was the case for this play.

Taking my seat on the ground level, to the centre and slightly below the level of the stage, I was struck by the intimacy of the Swan Theatre, a beautiful wooden framed hexagon style auditorium, with two raised galleries above me, every area providing excellent viewing of the stage. Built on the side of the larger Royal Shakespeare Theatre, the Swan holds about 450 people, and for this, the last night of The Jew of Malta, it was fitting that it was a sell out. Having been refurbished as part a larger £112.8 million project, the Swan is often used for playing the works of William Shakespeare’s contemporaries and other European writers, as was the case for this play.

Whilst the hearing in the audience were entertained by the orchestra, situated on the 2nd floor directly in front of me and above the stage, before the play started, I chatted to other Deaf people around me, with the hearing audience watching us, no doubt wondering (if they didn’t know) how we would understand what was going to be said on stage.

Set in Malta, the play was written over 400 years ago, and yet its themes of tribalism, racism, hatred, greed, revenge and misguided / misinterpreted religion, could apply equally in today’s society. Religious or not, the play challenges thinking, and through the religious themes it had attracted criticism, some quarters accusing it of being anti-Semitic.

Set in Malta, the play was written over 400 years ago, and yet its themes of tribalism, racism, hatred, greed, revenge and misguided / misinterpreted religion, could apply equally in today’s society. Religious or not, the play challenges thinking, and through the religious themes it had attracted criticism, some quarters accusing it of being anti-Semitic.

Having seen many BSL interpreted performances, with the interpreter dangled precariously on the edge of the stage out of the line of sight of most of the audience so as not to distract them, I was not sure what to expect by an RSC play that was promoted as having BSL integrated into it. I need not have worried.

Opened by Simon Hedger, who plays Machiavel, we are taken to Malta, a place which is threatened by invasion by the Turkish Empire, and immediately introduced to Becky the interpreter, standing to his side and interpreting the meaning of a bygone language, much of which is no longer used in British society. In costume, she blended seamlessly into the play, with many an on-looker unfamiliar with sign language, probably thinking she was simply one of the characters. Easily able to take in both the BSL and the characters, I relaxed knowing that this was going to be a fully inclusive experience for me.

Opened by Simon Hedger, who plays Machiavel, we are taken to Malta, a place which is threatened by invasion by the Turkish Empire, and immediately introduced to Becky the interpreter, standing to his side and interpreting the meaning of a bygone language, much of which is no longer used in British society. In costume, she blended seamlessly into the play, with many an on-looker unfamiliar with sign language, probably thinking she was simply one of the characters. Easily able to take in both the BSL and the characters, I relaxed knowing that this was going to be a fully inclusive experience for me.

Interestingly, some of the music, an important indicator of tribalism in the play, was also accessible to me, through the use of a large base drum, the vibrations from which I could easily feel, despite sitting two floors below.

Introduced to Barabas, a wealthy but murdering Jewish merchant played by Jasper Britton, a real connection is formed between his character and Becky the interpreter at the outset, a connection that he maintained throughout the play and for which he deserves much acclaim as this was the only performance done this way.

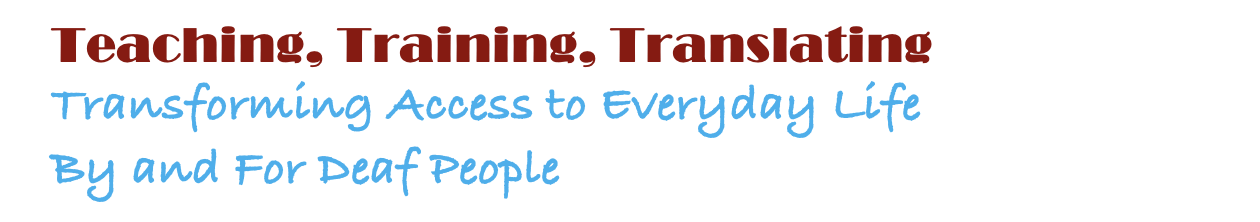

The heavy themes, underpinned by lies and treachery, are interspersed with brilliant comic moments, Barabas’ facial expression often signifying evil thought, in direct contrast to the words being spoken. At these moments with Barabas and his slave Ithamore, played by Lanre Malaolu, their facial expression on stage was so good, I felt I hardly needed to watch the interpreter to know and understand what was going on. Their face said it all!

The heavy themes, underpinned by lies and treachery, are interspersed with brilliant comic moments, Barabas’ facial expression often signifying evil thought, in direct contrast to the words being spoken. At these moments with Barabas and his slave Ithamore, played by Lanre Malaolu, their facial expression on stage was so good, I felt I hardly needed to watch the interpreter to know and understand what was going on. Their face said it all!

With one bad deed leading to another, and one lie having to be covered by another, we were taken on a spiral to despair, ultimately leading to Barabas being killed by the Christian Governor, Ferneze, played by Steven Pacey. Whilst proper order was resumed on the island of Malta at the end, there were no religious or cultural winners in this play, and yet you couldn’t help liking some of the characters.

The play as a whole was hugely enjoyable, a quite wonderful experience, especially for someone like me who was not given the chance to properly study the classics whilst at school. But let me turn my attention to the means by which this work of art was made accessible to me.

The play as a whole was hugely enjoyable, a quite wonderful experience, especially for someone like me who was not given the chance to properly study the classics whilst at school. But let me turn my attention to the means by which this work of art was made accessible to me.

Photo is copyright of the Royal Shakespeare Company.

The actor/interpreter Becky Allen was present throughout, with barely a moment to catch a breath. Her placement was varied from standing/sitting at the side of characters whilst on stage on their own, to using the elevated backdrop to gain height when more people were on stage. Whilst she did not play a character, it seemed for all intent and purposes that she was one, in effect watching the story unfold, and telling that story to the watching Deaf audience. Her facial expression, both when signing and simply observing was outstanding, each smile, gaze, quizzical and questioning look, helping me to understand what was going on.

Involved in comic moments herself, I cannot imagine the inclusion of integrated BSL ever being better than I had the pleasure of watching last night. For me, Becky’s BSL, performed as accurate interpretation and not some artistic expansion of our language, actually added to the character of Barabas enormously, expanding on his own wonderfully acted expressions of feelings and emotions. Being able to understand the BSL, I felt I was actually getting more out of the play than people who could not.

Involved in comic moments herself, I cannot imagine the inclusion of integrated BSL ever being better than I had the pleasure of watching last night. For me, Becky’s BSL, performed as accurate interpretation and not some artistic expansion of our language, actually added to the character of Barabas enormously, expanding on his own wonderfully acted expressions of feelings and emotions. Being able to understand the BSL, I felt I was actually getting more out of the play than people who could not.

For me, Becky and Justin Audibert have taken BSL theatre interpretation to a whole new level with a hearing colleague of mine who knows some BSL telling me, “This was so far away from tokenism as you can possibly get. I didn’t need the interpreter, but I found myself watching her at times anyway, as she added greatly to my interpretation of Marlowe’s words and my understanding of the main characters.”

At the end of the play, the director and some of the cast returned to the stage to give the audience a chance to ask questions. Asked about her role in the play and any difficulties she faced, I was astonished when she told us, “I had just one day to rehearse with the cast, although there had been many previous discussions.” It was so well done, and so brilliantly integrated, I found that comment just unbelievable.

Having heard the comment by theatre companies so many times before that BSL interpretation has to be out of the line of sight of the hearing audience, I took to the stage myself during this session to ask the audience whether they felt the BSL was an intrusion or a distraction. Amidst several positive comments ( and not one negative ), one gentleman said, “I don’t need sign language but it added to the occasion. It was lovely to have deaf people here to enjoy it with us, so I just have to say thank you for that.” Met with loud applause, everyone else present seemed to chime with that comment.

Commenting on that issue from a Director’s perspective, Justin Audibert said, “Yes that was a concern, so it was delightful to hear at the post show Q and A that actually it enhanced the performance for both deaf and non-deaf patrons alike. I have never directed an integrated BSL performance before and wanted to do it and knew that this would be a learning experience. I have some thoughts on how to do it better and hope to get a chance to put them into practice.”

With so few BSL integrated shows to learn from, I also asked Justin about the challenges BSL integration posed. “The key was establishing a language whereby the actors could interact with Becky or equally a language where that was not appropriate. We felt it worked well in scenes and with characters who talk directly to the audience i.e. Barabas, Bella Mira, Ithamore, but it didn't feel it would work to have actors interact with Becky when we were in the more conventional scenes which have more of a, "fourth wall" i.e. the scene's in Ferneze's court.”

The star of the show, Jasper Britton, who played the conniving Barabus, is a seasoned RSC actor. Commenting on the BSL integration which he managed so superbly on stage, he told me, “I've done one integrated BSL performance before, when I worked with RSC Deputy Artistic Director Erica Whyman, at Northern Stage in Newcastle. It was a very different play and production, but nonetheless effective with integrated BSL.”

The star of the show, Jasper Britton, who played the conniving Barabus, is a seasoned RSC actor. Commenting on the BSL integration which he managed so superbly on stage, he told me, “I've done one integrated BSL performance before, when I worked with RSC Deputy Artistic Director Erica Whyman, at Northern Stage in Newcastle. It was a very different play and production, but nonetheless effective with integrated BSL.”

“For me the beauty of last night was the immediacy provided by Becky and her amazing ability to be so responsive to what is a difficult and archaic text, and cope with us making demands on her intellect and emotion at the same time. I thought and felt that integrated BSL, provided by Becky, actually opened up the play, stories and characters far more, than if she'd simply been standing to one side, as is so often the case. As far as rehearsal is concerned, the less the better, if you are dealing with someone as skilled and sensitive as Becky. We could have happily spent much more time developing the integration, and found more ways to involve Becky.”

“It works very easily for characters who speak to the audience directly, so it wasn't a problem for me in any way. My first instinct was that it wasn't the right performance to integrate BSL into, being our final ride through the play, but the atmosphere of the day, the evening, and the celebratory nature of taking the play to another level on its last outing was sublime."

I know why I feel so elated as a member of the audience and so privileged to have been a part of Becky’s creative brilliance, but it was genuinely heart warming to get such positive comments from others in the audience, and even more so, from the cast and creative team. This was a play that included me - something that has been denied me many many times, and yet, as the genie came out of the lamp, it seemed everyone benefitted from the bold and creative steps taken by the RSC to give me proper access to their play.

I know why I feel so elated as a member of the audience and so privileged to have been a part of Becky’s creative brilliance, but it was genuinely heart warming to get such positive comments from others in the audience, and even more so, from the cast and creative team. This was a play that included me - something that has been denied me many many times, and yet, as the genie came out of the lamp, it seemed everyone benefitted from the bold and creative steps taken by the RSC to give me proper access to their play.

I want to thank everyone involved from the bottom of my heart, for making this such a wonderful, inclusive, deaf friendly night and I hope it is followed by many more.

Bravo RSC, Justin Audibert, Becky Allen and everyone else involved!

Some photos by Ellie Kurttz.

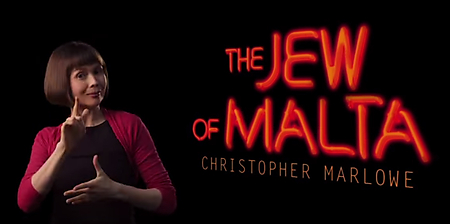

Article by Sarah Lawrence, Editor

posted in Entertainment / Stage, Theatre & TV

9th September 2015