The Snug4th December 2014

WWII Memories as a Young Lad

Now Hard of Hearing, Ernie reflects on his time growing up during the war

I was born in Pontypridd in 1930, but my father's work involved a move to the village of Pontnewydd in Monmouthshire in 1937 and it was here that I spent most of the war years. Pontnewydd may be a village, but it does not conform to the conventional idea of a pretty, rural setting. Situated in a shallow industrial valley mid-way between Newport to the South and Pontypool to the North, steel and other heavy industries were the main employers of the area.

As an eight year old, I was very aware that war was coming even if I didn't know why. Throughout that summer of 1939, war was on everyone's mind. We had a small Ford 8 saloon car and when school ended for the summer break, we headed off to Kent for a holiday as we had done the previous year. My mother's younger sister had married a coal-miner from Abertillery who in the 1930s, had moved to Kent to start a new coalfield. We stayed with them for a week or so, enjoying the excellent sea-side resorts in the area. This year, the journey was different, as we saw many military convoys and camps on our way and as we drove through London, I saw my first Barrage Balloons, large silver ‘elephants’ floating protectively above the city.

My Aunt lived just outside Canterbury, and even as an eight year old I was surprised that the main road took us across the R.A.F. Aerodrome of Manston, where aeroplanes could be clearly seen on the field with no guards in sight.

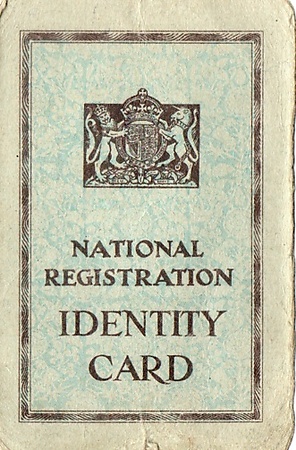

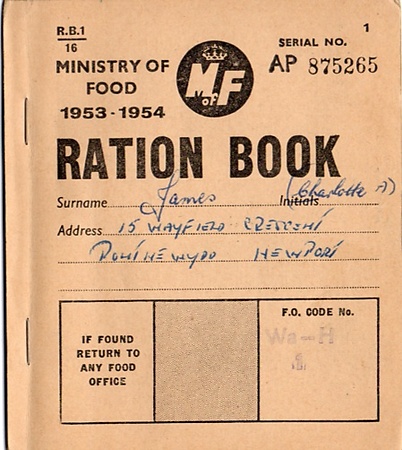

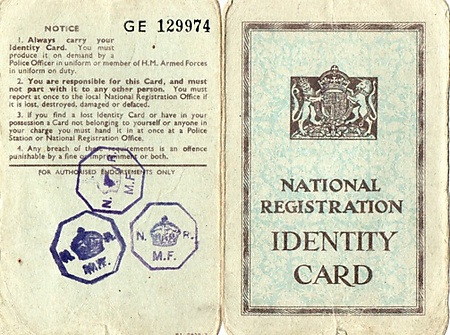

When we returned home everything seemed to happen all at once, collecting and fitting gas masks, getting individual Identity Cards and ration books. My mother was asked if she would take in an evacuee, she agreed and expected a boy of about my age. However, when the evacuees arrived from Birmingham about a week before war was declared, we were persuaded to take in two girls aged about 10 or 11. I lost my bedroom and slept in the ‘Boxroom’, but I was cosy and didn't worry about storing my clothes etc.

When we returned home everything seemed to happen all at once, collecting and fitting gas masks, getting individual Identity Cards and ration books. My mother was asked if she would take in an evacuee, she agreed and expected a boy of about my age. However, when the evacuees arrived from Birmingham about a week before war was declared, we were persuaded to take in two girls aged about 10 or 11. I lost my bedroom and slept in the ‘Boxroom’, but I was cosy and didn't worry about storing my clothes etc.

The girls were very nice, but although they both came from Ladywood, they did not know one another, so it was a bit of a shock for June who had never shared a bed before. Diane on the other hand had brothers and sisters so was used to ‘roughing’ it. They both soon settled in and my parents did everything possible to make them feel at home.

On Sunday September 3rd, we all gathered in the small living room to hear, “An important announcement form the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain”. We all knew what to expect but we all sat quietly looking at the wireless on a table in an alcove by the fireplace, where many years later a television set would sit. We listened as his now famous speech was made and when he finished with the words, “we are now at war with Germany”, I remember we all sat very quietly for a while. It all seemed so serious! Then my mother got up to continue getting the midday meal and we all dispersed. I went out to talk to other boys, all were excited, too young to really appreciate what was to come but life didn't change at all to start with, everyone carried on in a normal way.

Soon after we went shopping in Pontypool Market and we were surprised to hear a Military Band. In the main street we saw an army band ahead of two or three open trucks on which Army Sergeants were encouraging young men to jump on and join the army, “for King and Country”. I saw a few young men excitedly getting on the trucks and I have often wondered what happened to them. Did they actually join up when they calmed down? If they did, did they survive the war?

Coming from Birmingham, the two evacuees had never seen the sea, so one weekend my father drove us all to Barry Island where the girls had a great time in the sand and paddling in the sea, it was much too cold to attempt bathing. A few weeks later we drove to Birmingham for the girls to see their families. Again, my Father was doing his best to keep the girls happy and contented. This time it didn't work. Whilst Diane was quite ready to return to our home, June was not and was even more homesick than ever. A few weeks later her Father came to take her home and apart from the fun on Barry Island beach I had never seen her so happy.

Coming from Birmingham, the two evacuees had never seen the sea, so one weekend my father drove us all to Barry Island where the girls had a great time in the sand and paddling in the sea, it was much too cold to attempt bathing. A few weeks later we drove to Birmingham for the girls to see their families. Again, my Father was doing his best to keep the girls happy and contented. This time it didn't work. Whilst Diane was quite ready to return to our home, June was not and was even more homesick than ever. A few weeks later her Father came to take her home and apart from the fun on Barry Island beach I had never seen her so happy.

Diane later said that June had been singing, “Wish me luck as you wave me goodbye”, in the bathroom. The last I saw of June was her walking up the street towards the station with her father; she didn't turn around and wave and we never heard from her or her parents again, no letters, no Christmas cards, nothing. Many years later after the war, Diane met her in a street in Birmingham and June turned and walked swiftly away. On the other hand, Diane stayed with us for about a year and returned home when her father died. She regularly kept in touch and visited a few times after the war and when married brought her husband with her. Unfortunately, she died quite young in her 50’s.

When the evacuees first arrived, the Church School proved to be too small to accommodate both sets of children so to our delight it was decided that the local children would go to school in the mornings only and the evacuees would go to school in the afternoon. The following week we would change places. This worked well for a few weeks until some spoil - sport discovered that there were two chapels in the village which had rooms big enough to use as classrooms. Then we attended a chapel for one week in the mornings and the Church School in the afternoon. As before, we alternated with mornings and afternoons.

The ‘Blackout’ was something we all had to endure for almost all the war years. It would be difficult for someone today to understand how dark the nights were at this time. Air Raid Warden types like Hodges in Dads' Army, although a comic character, was a reality during the war. Almost every street had an A.R.P. Warden, his main job was to ensure that no lights could be seen from the air. The nights were so pitch-black that it was easy to get lost. One night we were sitting at home when we heard someone open our backdoor and walk in. It was a neighbour from two doors away, she had miscounted the buildings and thought she was going into her own home. Lampposts and other obstructions that might prove a hazard in the dark had white rings painted on them. Some people wore white armbands and I remember being given a small round badge to wear which glowed in the dark. Buses and trains had blacked out windows so you had to count the number of stops to ensure you got out at your destination.

During the time the evacuees were with us, nothing much seemed to be happening in the war. An American journalist called it, “A phoney war”, and with this peaceful time, most of the evacuees gradually drifted back homewards. Soon our schooling was back to normal with one or two evacuees fitting into our classes. We still practised putting on our gas masks in class about once a week, but looking back, even that was rather half-hearted but the teachers probably felt they had to maintain a standard.

During the time the evacuees were with us, nothing much seemed to be happening in the war. An American journalist called it, “A phoney war”, and with this peaceful time, most of the evacuees gradually drifted back homewards. Soon our schooling was back to normal with one or two evacuees fitting into our classes. We still practised putting on our gas masks in class about once a week, but looking back, even that was rather half-hearted but the teachers probably felt they had to maintain a standard.

I had put a map of the Western Front on my bedroom wall on which I could put the flags of the different armies. As with everything else, I had very little to change on the map until May 1940, when the Germans started their “Blitzgrieg” and raced through Holland and Belgium in no time at all. I listened to the radio and tried to keep moving the flags on my map but the German forces were moving so quickly I could not keep up. Then came the disaster of Dunkirk and the whole mood of everyone became very serious. Light-hearted jokes about the Germans disappeared and no-one sang, “We are going to hang our washing on the Siegfried Line” anymore. Air raid activity increased over the eastern part of the country but because the Germans now had airfields in France no part of Britain was free from aerial attack.

At school, we started to practice what to do if the Air Raid Sirens sounded. No Air Raid shelters were available in the area so when an ‘Alert’ sounded, all the children had to go home. One day, ‘Air Raid’ was called and dutifully we ran from school. When we reached the canal bridge a friend and I realised we had come without our coats so decided to walk back up the church path to collect them. As we entered the cloak room to collect our coats a teacher spotted us and shouted at us that we should not be there because this was a real air raid, not a practise and to get home immediately. It was all very quiet and we strolled down to the village where we went our separate ways.

As I walked down my street, I heard aircraft behind me and knew instantly that they were Spitfires – all young boys during the war could probably identify dozens of aeroplanes but the Spitfire sound was unique. A deep throaty kind of sound with a distinctive whistle – I turned and flying right over me were two Spitfires flying either side of an Avro Anson – a twin-engined general purpose aeroplane which could carry about twelve passengers (and in which in 9 years time I would make my first flight). Obviously, someone very important was in the Anson and they were flying towards Cardiff but more probably St. Athen's aerodrome, the largest and most important in Wales at the time.

I stood at my garden gate and watched them disappear, then realised there was a lot of “banging” from the direction behind the house. I ran to the back garden and was astonished to see a German bomber – a Heinkel IIIK – flying up the valley towards me heading in the direction for Pontypool – later I realised he was probably following the main railway line. All around the aeroplane were grey puffs of smoke where the anti-aircraft guns had fired at the plane. They continued to fire as I watched and one burst right under the aircraft lifting it up as though it had gone over a bump in the road. The plane was level with me and not very high because I could see all it's markings quite clearly. The pilot decided that the last explosion was too close for comfort and banked to it's right and flew away from me towards the Bristol Channel. It disappeared over the hilly part of Llanfrechfa as I watched it go out of sight, with the guns still firing at it.

I knew where the anti-aircraft guns were situated because I had cycled to the site with magazines, comics and other items for the soldiers to read. The following day in school there was much to talk about everyone having “seen” something the others hadn't. A rumour circulated later that day that the plane had been shot down over the Bristol Channel but there was never any official announcement to that effect.

I knew where the anti-aircraft guns were situated because I had cycled to the site with magazines, comics and other items for the soldiers to read. The following day in school there was much to talk about everyone having “seen” something the others hadn't. A rumour circulated later that day that the plane had been shot down over the Bristol Channel but there was never any official announcement to that effect.

Later that year I had the opportunity to visit and climb on board an identical aircraft that had been captured. For sixpence (2.5p), I was allowed on board, sat in the pilot's seat, went down into the nose where the bomb-aimer and front gunner lay and then up to the position of the mid-upper gunner. All the guns were on display outside the plane. The sixpence charge was towards the ‘Spitfire Fund’, for which there were constant collections and raffles because at the time a Spitfire cost £25,000 to build.

I only saw one other German aeroplane in daylight. The sirens had sounded and after a while I heard aircraft engines. Looking up I saw four or five planes in a very tight circle far above me. I could not identify them, but after a short time one broke away from the circle and dived quickly, closely followed by two of the other planes, they soon went out of sight. I learned much later that the tight circle formation was not one in which pilots liked to be involved because whilst none of the aeroplanes in the circle can fire at another, the one who breaks away first is the easier target. I assumed the one who broke first was probably German because of the need to have enough fuel to get home.

During this fairly quiet time, the sirens often sounded but nothing happened and one Sunday morning I was in my room reading when I suddenly realised I had been listening to the church bell for several minutes. The significance of this is that no church bells were to be rung except in the event of an invasion by the enemy!

I ran downstairs to find my Father already donning his Home Guard uniform prior to dashing to the Home Guard assembly point. I followed him out of the house and found the street full of neighbours, all in an excited state but not panicking. Lots of talking with suggestions and so on, but no-one knew what to do. People half expected to see German soldiers marching down the road.

After about an hour, the ‘All Clear’ sounded, all breathed a sigh of relief and wondered what had happened. Our next door neighbour had produced a shotgun we never knew he had so to get rid of his frustration he put a can on top of his fence and shot it off. My father returned home slightly peeved but enjoyed telling a story which could easily fit into the annals of the ‘Dads' Army’ programme. He had reached the Home Guard assembly point at the same time as others, however, they could do nothing because the officer who held the keys to the armoury had not turned up. After a reasonable time, someone went to get him. He had not heard either the sirens or the church bell. He finally opened the armoury but each rifle had to be signed for and the rifle number recorded, as was the single clip of ammunition which he reluctantly issued. When the ‘All Clear’ sounded, the entire process had to be reversed!

After about an hour, the ‘All Clear’ sounded, all breathed a sigh of relief and wondered what had happened. Our next door neighbour had produced a shotgun we never knew he had so to get rid of his frustration he put a can on top of his fence and shot it off. My father returned home slightly peeved but enjoyed telling a story which could easily fit into the annals of the ‘Dads' Army’ programme. He had reached the Home Guard assembly point at the same time as others, however, they could do nothing because the officer who held the keys to the armoury had not turned up. After a reasonable time, someone went to get him. He had not heard either the sirens or the church bell. He finally opened the armoury but each rifle had to be signed for and the rifle number recorded, as was the single clip of ammunition which he reluctantly issued. When the ‘All Clear’ sounded, the entire process had to be reversed!

The similarity with ‘Dads' Army’ was incredible, the Home Guard unit to which my father belonged was formed within the company he worked for. The bosses of this company decided to form the Home Guard unit making themselves officers without any experience or qualifications, while there were those amongst the ranks who had served in the First World War, one having a medal for Bravery.

The cause of the emergency? Instructions had been issued by the Government that German aeroplanes never carried more than five crew members, so that if more than five parachutes were seen it was to be assumed that it was a paratroop attack. A farmer's wife living on the mountain above Pontnewydd saw the German aircraft being fired at and thought she saw 6 or 7 parachutes coming from it. She ran down to the church where she told the vicar who proceeded to ring the church bell. Afterwards, it was assumed that she had mistaken the puffs of smoke from the anti aircraft shells for parachutes. At least it gave the village something to talk about.

I was a member of the St. Johns Ambulance Brigade at this time. We used to meet on Friday evenings where we were taught all about First Aid which was very useful then and for which I have been grateful ever since. Many minor injuries have been treated with the knowledge I gained then. We had a smart uniform to wear on special occasions, Black beret, grey shirt and socks and black short trousers. One Friday we were told to come to the Ambulance hut at the bottom of the church path on Sunday morning wearing our uniforms. A full scale Air Raid exercise was to take place and we as cadets were to be the ‘victims’ of a bombing raid. Our uniforms were to identify us.

I was a member of the St. Johns Ambulance Brigade at this time. We used to meet on Friday evenings where we were taught all about First Aid which was very useful then and for which I have been grateful ever since. Many minor injuries have been treated with the knowledge I gained then. We had a smart uniform to wear on special occasions, Black beret, grey shirt and socks and black short trousers. One Friday we were told to come to the Ambulance hut at the bottom of the church path on Sunday morning wearing our uniforms. A full scale Air Raid exercise was to take place and we as cadets were to be the ‘victims’ of a bombing raid. Our uniforms were to identify us.

On the Sunday morning, we assembled as asked and had labels tied to our tunic stating what our ‘injuries’ were. I was disappointed to find I only had a ‘broken arm’. We were then driven to Upper Cwmbran, a part of the area I didn't know. We stopped by a pair of derelict cottages which looked as though they had been bombed. An incredible coincidence but those cottages were 50 yards from where I now live and the one building was where my detached garage now stands.

There were about ten of us cadets and we were led into the cottages very carefully, no real accidents were wanted. I was told to sit amongst some rubble in the corner of an old fireplace. One cadet was asked to lie on a tarpaulin because he had serious ‘injuries’ ‘broken arms and legs’ and when he was in position, ‘wreckage’ was very carefully placed around him so that the Rescue teams would have to free him. After everyone was in position, a smoke bomb was ignited to give the impression of burning buildings. Soon after, we heard the bells of the fire engines and ambulance approaching. The firemen ran hoses through the houses into the stream that ran (and still does) nearby. Unfortunately, in their haste, someone did not check that the hoses were properly connected and when the fire pump started the pressure of the water forced one connection open and the cadet lying in the ‘wreckage’ was soaked and didn't find it as funny as we did later. He got top priority in being rescued and had the luxury of an ambulance all to himself.

A voluntary nurse ‘found’ me and gently treated me as though my arm was really broken, she then helped me out of the cottage to a waiting car and with another cadet was driven back to the Ambulance Hall. There a Doctor examined my dressings, they were then removed, I was given a cup of tea and a biscuit and sent home with thanks.

On another occasion we were told to attend the Ambulance Hall in uniform where a senior officer of the Ambulance Brigade presented each one of us with a box of goodies sent to us by the American Junior Red Cross. Different schools and organisations in America had donated to this scheme. My box (about the size of a shoe box) was filled by the pupils of a school in the Bronx, New York. The contents of each box were of course different, in mine was a bar of chocolate, a bag of candy (sweets), a small tin of Spam, a tooth brush, toothpaste, pencils, a few note pads, a net of glass marbles, some small items for board games and a bar of perfumed soap. The smell of the soap stayed with the box until I threw away the box after nearly 60 years. The only item remaining is the net of glass marbles.

On another occasion we were told to attend the Ambulance Hall in uniform where a senior officer of the Ambulance Brigade presented each one of us with a box of goodies sent to us by the American Junior Red Cross. Different schools and organisations in America had donated to this scheme. My box (about the size of a shoe box) was filled by the pupils of a school in the Bronx, New York. The contents of each box were of course different, in mine was a bar of chocolate, a bag of candy (sweets), a small tin of Spam, a tooth brush, toothpaste, pencils, a few note pads, a net of glass marbles, some small items for board games and a bar of perfumed soap. The smell of the soap stayed with the box until I threw away the box after nearly 60 years. The only item remaining is the net of glass marbles.

It was a lovely gesture by the Americans and of course I wrote to the school expressing my thanks. I never received a reply and it only dawned on me quite recently that during the war, all normal mail went across the Atlantic by ship and at the time U-Boats were having a great time sinking ships and my letter may well have not been received.

All these events took place in 1940, when as I have said, it was fairly quiet for us in this part of Britain. However, all this was to change. London and many of the large cities had been attacked quite frequently at night. With the R.A.F. success of the Battle of Britain, the Germans had discovered that the skies over this country were not safe in daylight and so night attacks became commonplace for most of the rest of the war. The night-time ‘Blitz’, in this part of the world, started with raids on Newport, Cardiff and Swansea in the New Year.

Because of the shortage or lack of air raid shelters for the civilian population, the Ministry of Information offered many suggestions, one of which was that under the stairs was one of the safest places to go during a raid. Apparently, it was a strongpoint in the construction of a house. For the first few air raids we experienced, my mother and I sat on chairs in our pantry which was under our stairs. This was not very comfortable and since no bombs seemed to be coming our way, we soon stopped sitting there. We were very conscious though of what the people of Newport, Cardiff and Swansea were going through. The explosions of bombs dropped on Newport and even Cardiff made our house reverberate.

Often, it seemed as though the Bomb had landed in our street. Of course, it hadn't, but the noise and concussion made us feel that it was that close. It was a long time ago and my memory may be faulty, but it seemed as though those raids occurred every night for weeks and weeks. One night I heard the distinctive sound of a German ‘Stuka’ dive-bomber. The plane had a siren fitted so that when it went into a dive a frightening screaming sound came from the aircraft.

Sometimes, I was allowed outside to see the sky illuminated by the fires from the towns being attacked. Even Swansea, 60 miles away, lit up our area almost like daylight. When Cardiff was having a particularly bad bombing night, my father called me out to see the German bombers circling overhead before making another bomb run towards the city. Most of the time, however, I was lying under the very strong dining table where my parents had created a comfortable bed for me. The raids went on until the early hours of the morning. It was not uncommon for me to fall asleep and wake up still under the table. Usually, I was taken back to my bed when the ‘All Clear’ sounded.

During the day, life carried on as normal as possible, school or work and so on. Shopping, however, was different. Families had to register with a particular shop for their food supplies. (see supplement on Rations). A few times, I went to get our weekly allocation of rations instead of my mother and I hated it. Because I was a little boy, I was frequently ‘elbowed’ out of my place in the inevitable queue, by women who insisted they were busy or used some other excuse. It was quite normal to wait an hour to be served. The shopkeepers had their favourites with serving and amounts of food. Even at my young age, I thought that they would regret this attitude and I am pleased to say that when rationing ended after the war, some of the shopkeepers found that their trade dropped considerably.

In one respect, as a family, we were lucky because the farm at the bottom of the field supplied us with milk and eggs without fail. Every day the farmer came with his horse and cart with the milk. Churns of fresh milk were on the cart and the farmer would come to the door with a small churn and a pint measure and while he poured milk into your jug the horse would move slowly up to the next house. If we ran short of milk or eggs, I would walk down to the farm, knock on the farmhouse door and ask for milk or eggs. I would be taken to the dairy where I would get what I wanted. Often warm eggs and warm milk.

As a little boy I was never conscious of being hungry, bread was still delivered daily it was not rationed until after the war! But, it was not until I was older that I discovered that my mother gave me her butter ration whilst she had margarine and I am sure this probably applied to other things as well.

In 1942, I passed the Scholarship examination and started at West Monmouth Grammar School in Pontypool. This meant travelling by train every day, which I did until 1948 and the good old reliable ‘Push and Pull’ never failed to arrive, even in the worst weather. In the dark winter days, the only illumination on the railway stations came from a few dimly lit blue lights. This was to stop enemy aircraft from pinpointing railways which could lead them to their targets. After the war, I read that some allied airman would fly low enough to see the shining railway lines which would help them. The ‘Blackout’ was something that I don't think we ever got used to.

Unlike the Junior School, I only remember one ‘Air Raid’ drill when the whole school assembled on the lawn. It took so long to organise I believe that is why it never occurred again. For a while, we still carried gas masks, but even this was not insisted upon and daily school life was not very different from what I experienced after the war ended. The only significant factor was that for a Boys' school, only about four men teachers were at the school, all the rest were women. However, as soon as the war ended, male teachers quickly replaced the women with one exception, a teacher so good she could not be easily replaced.

1942 was a turning point in the war in many ways. The Germans were driven out of Africa and Sicily, the U-Boats were being hunted more efficiently, British and American bombers were continually attacking targets in Germany and the Russians were driving the Germans out of their country. For me, life carried on quite normally. In the school swimming pool I learned to swim and during the summer holidays spent much of my time with my Grandparents in Pontypridd so that I could spend almost all day in the excellent outdoor pool that kept going despite the war.

The local cinema stayed open throughout the war, changing the program mid-week and it was here that we managed to see the newsreels that kept us in touch with what was happening. There was a matinee for children on Saturday afternoons, 1d (one penny) for the front seats and 2d for the rear seats. The films were not all that good, cheap Hollywood cowboy sagas and some slapstick comedy features. Order was kept by a large ‘Bouncer’ who marched up and down shouting at any unruly members of the audience.

I visited my Grandparents in Pontypridd as often as I could, travelling via three trains, all ‘Push and Pull’. In 1944, I discovered that my grandparents had a young couple living in the front part of their house. The man Hugh, worked for the Government War Agricultural Board, which helped farmers produce as many crops as possible. At this time, not every farmer could afford a tractor, so Hugh's job was to go to farms with his tractor and any other equipment needed and help the farmer develop more uncultivated land. He asked me if I would like to accompany him and I soon found myself sitting on the back of his trailer which carried all his fuel, heading towards a farm above Pontypridd.

I visited my Grandparents in Pontypridd as often as I could, travelling via three trains, all ‘Push and Pull’. In 1944, I discovered that my grandparents had a young couple living in the front part of their house. The man Hugh, worked for the Government War Agricultural Board, which helped farmers produce as many crops as possible. At this time, not every farmer could afford a tractor, so Hugh's job was to go to farms with his tractor and any other equipment needed and help the farmer develop more uncultivated land. He asked me if I would like to accompany him and I soon found myself sitting on the back of his trailer which carried all his fuel, heading towards a farm above Pontypridd.

I was lucky on my first trip, because it was harvesting time and was given the (enjoyable) task of sitting up on the ‘Binder’ which cut the corn onto a moving belt which was fed into a channel to be tied and then ejected, ready for stacking. My job was to watch the sheaves as they left the Binder to ensure that they were tied in the middle, if they weren't, I had a simple lever to operate which would change the position of the string. When we finished the field, I would help others in picking up the sheaves and stacking them into conventional Stooks. It was an enjoyable few weeks.

Throughout that season in the school holidays I helped with ploughing, discing and sewing. It was a great time for me. Probably the best memory I have, was when we were ‘discing’ the soil. For some crops, when the earth has been ploughed, the furrows must be broken down for the seed to be scattered. Towed behind the tractor was a heavy steel frame with steel discs set at different angles, so that when they pulled along they would break up the soil into fine particles. One day, we were on a very large farm where one of Hugh's colleagues was also working. He wanted to have some time off and offered me the chance to drive his tractor and ‘disc’ the field he was working on. I was delighted. My father was a mechanic and I had learned to drive on private land since I was big enough to reach the pedals. Hugh had also given me a few tries on his tractor so I was able to do the job. The old Fordson tractor was not difficult to handle, top speed was no more than six miles per hour, and to change gear you had to stop. With discing, there was no need to follow a particular course, the whole point was to break the earth up, so I had a wonderful few hours going this way and that making all sorts of patterns. Hugh in the next field kept an eye on me.

That was my contribution to the war effort and how I enjoyed it.

That was my contribution to the war effort and how I enjoyed it.

The war was reaching the final stages and in May 1945, Peace in Europe was declared. To celebrate, street parties were organised in every corner of Britain. Our party was held in the farmer's field and a great time was had by all. Some weeks later I went to visit my Aunt and Uncle in Kent. One night my Uncle woke me up at about 1.00 a.m. When I asked what was the matter he said, “The war is over, Japan has surrendered, come and celebrate”. I wanted to go back to sleep, but I went out to find the whole mining village on the streets, having a great time. I eventually got back to bed and that is how my war ended.

Article by E.W. James

posted in Deaf Lifestyle / The Snug

4th December 2014